I had been enlisted to help AFBI’s scientists on their October groundfish survey. These surveys contribute towards assessments of commercially important, demersal (bottom-dwelling) fish stocks in the Irish Sea, as well as other species that are caught by these trawls as by-catch. The information gathered is vital for ongoing monitoring and management of these populations, including the designation of TAC (Total Allowable Catch) quotas .

Adrift on the Irish Sea – A Shark Hugger’s Paradise!

The objective of the cruise was to visit 62 different sampling stations throughout the Irish Sea and conduct a 20 minute trawl at each site. These sample tows would give us an idea of how fish stocks were doing across the Irish Sea, and how they should be managed in future. As the overall cruise was running from the 2nd to the 20th of October, it had been divided into two legs. I was taking part in the first leg, swapping over with my fellow trainee Patrick, who was helping out on the second leg of the survey.

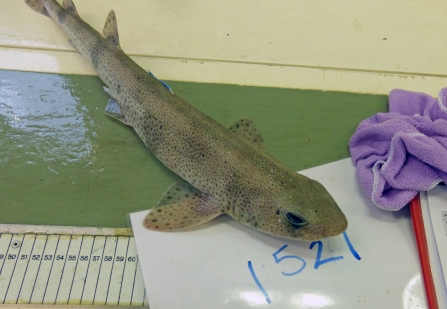

As well as helping with the groundfish survey itself, Patrick and I were tasked with an exciting and pioneering opportunity of tagging elasmobranchs (sharks, skates and rays!) that are frequently caught in these trawls. Unlike bony fish, elasmobranchs tend to show higher post-trawl survival rates – so there is normally a concerted effort to return them to the water as soon as possible. Elasmobranch conservation has been of growing concern over the last number of decades, as members of this family tend to exhibit slow growth rates, long gestation periods (pregnancy), late sexual maturity, and low numbers of young – all of which make them particularly vulnerable to overfishing. Whilst there aren’t many fisheries specifically targeting elasmobranchs in our waters, they do tend to be caught as by-catch in other commercially important fisheries.

Tagging programmes monitoring elasmobranch populations are already in effect in Scotland, however, this project would be the first of its kind to monitor populations around the coast of Northern Ireland. With this in mind, we were excited to be among the first to test out our new tags and training (although some of my enthusiasm can be traced back to the fact that I’m a massive shark nerd)!

On an average day, we covered between 4 and 6 tows. They varied greatly in size and content and some were much easier to sort through than others. Over time I got my eye in for noticing the subtle differences between similar species (like sprat and young herring, or poor cod and Norway pout) and our sorting time significantly decreased, and by the end of the 1st leg, we were working through the catches like a well oiled machine.

I was absolutely fascinated by every new species that came up in the net – and every fish was called some variation of ‘beautiful’, ‘gorgeous’ or ‘cute’ – regardless of whether it was a dinky dragonet or a monstrously large monkfish, much to the amusement of my fellow crewmates. Some of the most common commercial species that turned up were whiting, haddock and plaice. For these species, it was important to get more biological information such as a sample of length frequencies, parasite burden and stomach contents. Other species that frequently showed up in tows included sprat, herring, mackerel (Atlantic and Horse), gurnards, dragonets, nephrops (Dublin Bay prawn), Queen scallops, curled octopus and various types of squid and crabs.

Another common sight was our lovely elasmobranchs, the most frequently occurring by far being the lesser spotted dogfish (Scyliorhinus canicula). I had the opportunity to tag a number of other species, including starry smoothound, bull huss, tope, thornback ray and blonde ray. As mentioned previously, I’m quite a shark enthusiast, so I was exceptionally mothering of every shark and ray I had the opportunity to handle!

I also had the opportunity to extract otoliths from haddock and whiting. This fascinating (and somewhat gruesome) task required the retrieval of two small structures made of calcium carbonate (the otoliths) located in the inner ear of the fish. These structures are used by scientists to age fish and assess growth rate, but are important in fish for balance and orientation.

Spending a week on the sea had other benefits – I marvelled as a large pod of common dolphins cruised playfully alongside the ship, while exceptional weather off the coast of Wales made for some nice relaxation in between tows on our second last day. We were frequently tailed by big groups of gannets hoping to score some leftover fish – a particularly favourite sight of mine. Cackling in unison when fish were tossed into the ocean, several would dive acrobatically to pursue their dinner beneath the waves. Whilst the ship’s rocking and rolling could sometimes be a little disconcerting in the evenings, on most nights it was a comforting way to be lulled to sleep. However above everything else, the food was exceptional AND plentiful. I was so well fed, I was briefly concerned that I would have to be rolled off the ship come the end of the first leg. However, I found these fears were easily remedied by simply eating more and thinking less.

All in all, it was an exceptionally valuable and enjoyable experience and we tagged 4 rays and 68 sharks. I learned loads, got up close to animals I had only ever seen in pictures before, all the while contributing to meaningful and vital work. So many thanks to AFBI for hosting me, and to my fellow crew who taught me a great deal and who were also fantastic craic all round. Here’s to the next groundfish survey!